State Law → Local Code

Confirm what your municipality adopted and how it’s implemented.

Translate policy into the build envelope and review workflow.

Washington’s HB 1110 is a statewide middle-housing law that raises the legal ceiling on what many cities must allow in traditionally single-home neighborhoods—often 2, 4, or 6 units per lot, depending on jurisdiction tier, transit proximity, and affordability provisions.

This matters everywhere in Washington, but the reason it’s a “Seattle” trap is practical: the Greater Seattle market(Seattle + Eastside + much of King/Snohomish/Pierce) has the combination of land values, demand, and builder activity that makes the new density feel like an automatic paycheck.

It isn’t.

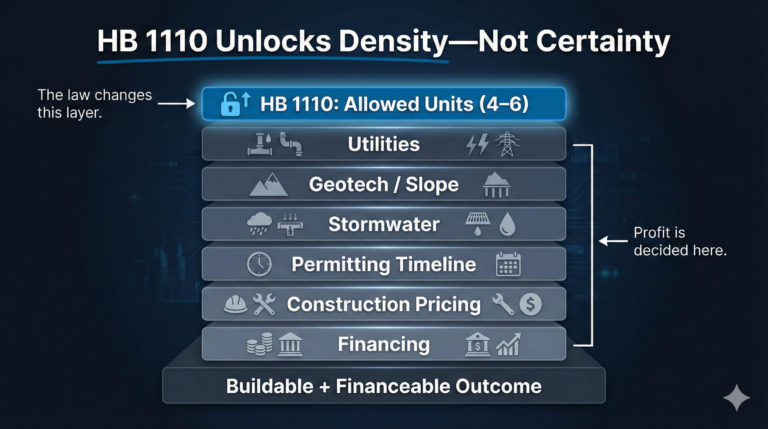

HB 1110 increases permission. Profit still depends on utilities, geotech, schedule risk, contractor pricing, and whether the project can be financed on senior-debt terms.

HB 1110 is statewide; outcomes are municipality-specific because cities implement it through local code (standards, review steps, setbacks, tree rules, stormwater, and timelines).

The “headline” uplift (often 4 units, sometimes 6) does not solve the constraints that make projects fail: utility scope, slope/geotech, and construction financing.

“Major transit stop” is defined in state law, and the “near transit” unit bump typically hinges on ¼-mile walking distance in many implementations.

The affordability pathway can require affordability to be maintained for at least 50 years via recorded restrictions, which changes underwriting and exit value.

Options and developer-controlled contracts are not inherently bad; they exist because entitlements are risky and capital is expensive. The risk is long exclusivity without verified feasibility or aligned milestones.

Owners capture the most upside when they treat HB 1110 as an execution problem: local code → site constraints → contractor cost truth → senior-debt readiness.

HB 1110 is Washington’s “middle housing” mandate: it requires many jurisdictions to allow a broader range of housing types in areas previously dominated by detached single-family zoning—duplex through sixplex formats, townhouses, stacked flats, courtyard apartments, and cottage housing.

Direct implication for landowners: HB 1110 can increase the highest-and-best-use of a parcel, but only if the site can physically and financially support the additional units.

These are the clauses that change the game in Greater Seattle—while also creating the trap.

Allow “at least 4 units per loton all lots zoned predominantly for residential use…” (Sec. 3(1)(b)(i))

“The development of at least six units per lot… within one-quarter mile walking distance of a major transit stop…” (Sec. 3(1)(b)(ii))

“To qualify as affordable housing… maintained as affordable for at least 50 years… [with] a covenant or deed restriction.”

“Shall not require off-street parking… within one-half mile walking distance of a major transit stop” (Sec. 3(6)(d))

And “major transit stop” is not subjective. State definitions include (among others):

Commuter rail stops… rail or fixed guideway systems… [and] bus rapid transit routes. (Sec. 2 amending RCW 36.70A.030)

Why these quotes matter: they increase theoretical yield, reduce one traditional friction point (parking near transit), and create a defined path to 6 units—while introducing new underwriting variables (distance tests, affordability covenants, and local implementation details).

Source: https://lawfilesext.leg.wa.gov/biennium/2023-24/Pdf/Bills/House%20Passed%20Legislature/1110-S2.PL.pdf

HB 1110 answers: “What is the city required to allow?”

Your return is decided by: “What is the site required to absorb?”

More units usually means more intense utility and stormwater scope. HB 1110 itself anticipates that some parcels won’t have “adequate water and public sewer” and allows density reductions in those contexts.

In Greater Seattle, this is where “6 units” quietly becomes “6 units with an unplanned civil budget.”

Many infill sites carry slope, landslide, or soils complexity. The unit count can go up while usable build area and cost efficiency go down.

The result is a common failure mode: more units, worse margin.

Senior lenders lend on:

entitlement clarity,

contractor-validated cost,

schedule realism,

and exit plausibility.

HB 1110 may improve the entitlement ceiling, but it doesn’t reduce uncertainty enough to make lenders fund a concept without disciplined preconstruction proof.

It’s worth saying plainly: developers aren’t villains. Options, PSAs with feasibility periods, and delayed closings exist because:

entitlement timelines are uncertain,

carrying costs are real,

and capital has an opportunity cost.

In many cases, a developer relationship is the right outcome.

The risk is structural, not moral.

Owners typically lose leverage when exclusivity runs longer than the verified feasibility. If the agreement gives 12–24 months of control while the project is still unpriced, ungeoteched, or utility-unknown, you’ve effectively sold the best part of the upside—time and optionality—before the value is proven.

If you’re evaluating an option or long feasibility period, look for:

Clear milestones (survey/utility confirmation, geotech, schematic set, contractor pricing, permit strategy) with dates.

Transparent go/no-go triggers tied to cost and yield.

Compensation for time (not just a hopeful price later).

Defined plan for what happens if they exit (data transfer, reports delivered, rights clarity).

This keeps the relationship pro-developer while still protecting the owner’s economics.

A 6-step sequence that turns “allowed density” into a lender-grade project.

Confirm what your municipality adopted and how it’s implemented.

Translate policy into the build envelope and review workflow.

Utilities, access, trees, and stormwater scope.

Geotech/slope + critical areas that govern cost and yield.

Select a unit mix + massing that matches constraints.

Avoid “density wins” that create expensive complexity.

Early pricing + value engineering before sunk design costs.

Output: credible budget range + risk flags.

Rebuild the model with real costs, timeline, and exit sensitivity.

Output: “financeable or not?” decision clarity.

Package entitlement clarity, budget credibility, and exit logic.

Output: executable capital stack path.

In Greater Seattle, added density can expand owner outcomes beyond “sell as-is”:

Sell at a higher residual value (because the buyer can pursue more units).

Joint venture with a developer (sharing upside rather than selling it all).

Owner-controlled development (the highest upside, but only if you can manage entitlement, costs, and capital).

The law is meaningful because it increases your menu of exits—not because it guarantees any one exit will pencil.

HB 1110 is a real statewide shift, and it creates real earning potential—especially in Greater Seattle.

The trap is confusing:

legal capacity with buildable capacity, and

buildable capacity with financeable returns.

If you want to stay pro-developer and pro-opportunity, the most reliable posture is simple: validate feasibility early, align cost with contractors early, and don’t give away time and control before the numbers are real.

Subscribe to our email newsletter full of inspiring stories, past projects and future investment opportunities.

All Rights Reserved © Copyright – GIS Development Corp